showCASE No. 119: Urban Farming: A Major Trend Shaping the Future of Resilient Cities

Editorial

The Covid-19 pandemic has once again showcased the importance of the resilient food supply chains and put forward the need to re-evaluate urban environments and regenerate our streets, parks, and unused spaces.

Against this background, in this edition of showCASE, we discuss the rising trend of urban farming and its potential in establishing greener, more inclusive and resilient local ecosystems.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

CASE Analysis

Written by: Karolina Zubel

Almost 70% of the world's population is expected to live in cities by 2050 according to the United Nations (UN) World Urbanization Prospects. In fact the RUAF Global Partnership on Sustainable Urban Agriculture and Food Systems – a consortium of experts working towards promotion of sustainable agriculture – estimates that rapid population growth coupled with global urbanisation will contribute to poverty and food insecurity if not addressed properly.

RUAF believes that urban agriculture can be crucial to feeding these new city dwellers. Indeed, according to a 2018 study published in the journal Earth's Future, urban farms can bring us as much as 1.87 billion tonnes of food a year – or about 10% of the global production of vegetables. Some more optimistic scenarios predict that the number could even reach up to 20%.

What is more, urban agriculture shows great potential in the fulfilment of basic human needs as it not only provides fresh food supplies, but also ensures a sustainable distribution system thereby creating new jobs and regular income for individuals. It also helps countries in environmental protection and saving on transaction and transportation costs.

Although major urban groups (i.e., elderly, youth) have already been vulnerable to growing food prices[1], the Covid-19 crisis exacerbated the vulnerability of other groups, including those who lost their jobs or part of their income and became at risk of malnourishment.

A Well-rooted Practice in Times of Crisis

Yet, it is worth noting that the coronavirus outbreak is not the first time that concerns about food (in)security have led to a tangible development of “kitchen gardens”. In fact, their history dates back to the beginnings of the 20th century. During World War One, the concept of “Victory Gardens” was highly promoted to prevent food shortages and losses in the United States (US) and United Kingdom (UK), among others. The effort continued during World War Two, with fruit, herbs and vegetables gardens in private and public spaces as well as the White House itself. Due to permanent food shortages, urban gardening was also common in most communist countries with some of them still being preserved (e.g. next to Biblioteka Narodowa in Warsaw).

The Covid-19 pandemic once again sparked interest in local produce and the benefits related to the community building. Experimental and inclusive endeavours where urban farms are developed indeed could become a mitigation action, or even a shock absorber during such disruptions, especially for those most vulnerable. In this sense, urban farming capacity becomes the city’s “insurance policy” in the event of future shocks or disasters that disrupt food supply chains.

While it is agreed that urban agriculture will always be a smaller part of our food supply system than traditional agri-techniques, it has an important role to play in the sustainability of urban and peri-urban areas.

Benefits of Urban Farming

Urban farming has much to offer in the wake of the pandemics and beyond. It could help local communities boost the resilience of their food supply, improve the overall wellbeing of residents, and help them lead more sustainable lifestyles, among others. The following five reasons can serve as a starting point.

1. Greener and richer urban ecosystems

Bringing urban farms into the city comes with more greenery closer to urban dwellers. Despite the fact that Covid-19 lockdown helped in boosting interest in cultivation of vegetables and herbs at home, most of households have no access to a garden. Urban farming omits this problem as city’s rooftops, walls, and abandoned containers provide a suitable space for food production, while creatively redeveloping the urban tissue in a sustainable manner.

Urban greenery can also help to reduce flood risk, provide natural cooling for buildings and streets, and help reduce air pollution. What is more, while rapid urbanisation has proved to be one of the biggest threats to biodiversity, growing food in cities is strongly believed to support the abundance and diversity of wildlife, as well as protect their habitats. For example, a recent study published in “Nature Communications” found that urban farms act as hotspots for pollinating insects.

2. Resilient fresh food supplies

Diversifying supplies will make potential risk of food-related interruptions smaller. The food supply chains disruptions encountered during Covid-19 outbreak, predominately in developing countries, might not have been as serious if urban farms were growing fresh and healthy food closer to city dwellers.

3. Job creation and skills development

The International Labour Office (ILO) predicts that growing urban farms will need a growing number of employees or volunteers.

Not only highly skilled planners can benefit from such developments. Urban farms can offer low-skilled citizens valuable skills, i.e. in a form of tailored trainings and workshops and effectively a steady source of income.

Hunger or malnutrition as well as poverty are common themes in world’s cities but urban farms could help to support the vulnerable groups holistically and secure their social protection.

4. Health and overall wellbeing

Plants cultivation has a positive impact on citizens mental health and overall physical fitness. When urban citizens have greater access to fresh fruit and vegetables and getting outdoors and into the greenery, their stress level reduces. It has also been proved that getting involved in urban food production may lead to choosing healthier diets – there are studies proving that urban food growing directs attitudes towards sustainability so that people place more value in produce that is healthy and organic.

5. Less waste

According to Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) a significant percentage of food waste results from grocery stores’ inefficient planning – they simply stock more fresh food than they can sell before it becomes inedible. Consumers are equally to be blamed – they buy the amounts their households are not able to consume (around 53% of all food waste). Urban farms can limit the scale of both problems as people will harvest only what they are going to eat within a day or two. A recent study from Turku University confirms that restaurant waste is also reduced and that the leftovers can be used for composting purposes.

These are just few important reasons that should compel local authorities to scale up food production in their respective towns in cities. Covid-19 has given us cause to re-evaluate how important resilient food supplies and local urban green spaces are, and why we can transform and regenerate our streets, parks, and unused spaces. The opportunity is there for local authorities to consider what ushering farming to urban landscapes could offer.

Different Forms, Same Goal

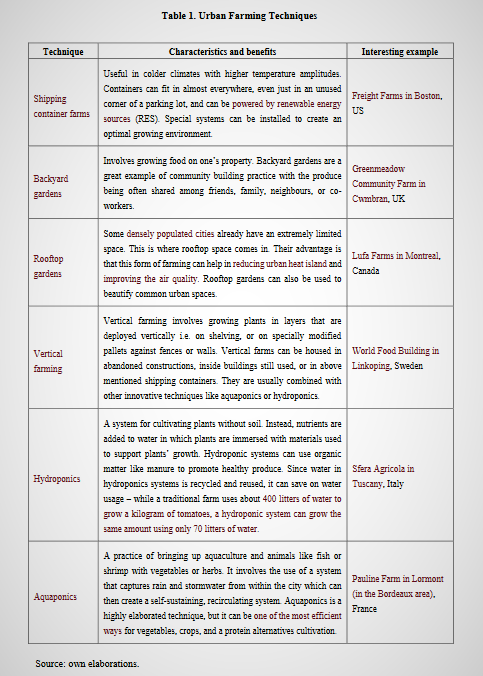

Urban farming can be practiced in different forms and environments and via different technologies, depending on the city’s geographical location and preferences, among others. The most common techniques are presented in the Table 1 below.

Other urban farming methods may include cultivation of microgreens or mushrooms, greenhouses, forest gardening, or tactical gardens, among others.

Experimental Governance, Transformative Thinking, and Urban Living Labs

Given local peculiarities, each urban farm should be created in a way that answers the local needs and boosts local climate adaptation and mitigation endeavours. With this rule in mind, CASE will soon kick off a project entitled “USAGE – Urban Stormwater Aquaponics Garden Environment” which aims to create the green-garden installation for the food production based on aquaponic system supported by rain and stormwater collection infrastructure in two European cities (Wroclaw and Oslo). The installations will play an educational and social role, integrating local citizens, creating the workplaces, and propagating the environment-friendly behaviours.

The project will take the Urban Living Lab (ULL) approach with six interrelated, feedback-driven work packages. As the ULL systemic approach is deeply rooted in the Scandinavian participatory design movements from the 1960s and 1970s, the ULL methodology within USAGE will move almost all research activities to the project sites. In this “co-creation” process, subject infrastructure will be developed in front of the local community and with their engagement.

What is more, two cities which will most likely encounter different problems in the pilot phase (i.e. not enough rain and stormwater in Wroclaw, bigger energy needs for the Oslo-based installation due to lower temperatures) will regularly share their lessons learnt and best practices with fellow pilot city what will most likely build their reputation of truly transformative urban centres. Follow our work to stay up to date with this experimental process insights and our main discoveries on sustainable urban farming practices.

Conclusions

The Covid-19 outbreak is a reminder that disruptions to food supplies can take place at any time making a strong case for urban farming uptake in towns and cities around the world. As the public interest in cultivating edible plants at home has soared, combined with heated discussions on bottom-up climate adaptation and mitigation strategies, a timing for local authorities to pursue tailored initiatives promoting urban farming has never been better. Cultivation of vegetables and fruits closer to urban dwellers is not only a requirement for a resilient city of the future, but could also improve communities’ overall health and fitness and help them in leading more sustainable lifestyles.

[1] related to transportation costs and environmental shocks among others.