Before We Close Tax Gaps, We Have to Understand Them

By: Tomasz Tratkiewicz, CASE Senior Economist

The subject of tax gaps has recently been of great interest not only to ministers of finance, the European Union (EU) institutions, international organisations, and research institutes, but also entrepreneurs and ordinary citizens. Tax gap is generally defined as a difference between theoretical revenue from underlying economic activities and the actual revenue. Tax gap can be decomposed into two main components: compliance gap and policy gap. While policy gap can be defined as an additional tax revenue that could theoretically be generated by applying a uniform rate on all goods and services, in this article careful considerations will be given to the compliance part of the gap, as this area allows for the development of a more or less unified approach to the methods of gap estimation. The key element in the compliance component is effective collection of taxes, which is the cornerstone of a fair taxation system. Taxes that remain unpaid mean revenue loss in the national budget, and they may reduce expenses on crucial socio-economic goals. Persistently unpaid taxes may lead to an excessive burden eventually borne by honest taxpayers due to higher compliance costs (when the government introduces additional requirements to fight tax frauds) or higher taxes (when the government needs to cover the budget needs quickly). Excessive burden can also weaken the willingness to pay taxes even by honest taxpayers. Effective collection of taxes is therefore essential to maintain the level playing field and to avoid economic distortions. Tackling the issue of unpaid taxes is thus a collective responsibility, which starts with understanding of the scale and the scope of the issue, but also includes understanding of the reasons for not paying taxes. In order to investigate the reasons for the non-payment of taxes, one should start by assessing and identifying the areas in which this phenomenon occurs at the largest scale. Estimating tax gaps helps in this matter.

A Quick Look at the History of Estimating Tax Gaps in the EU

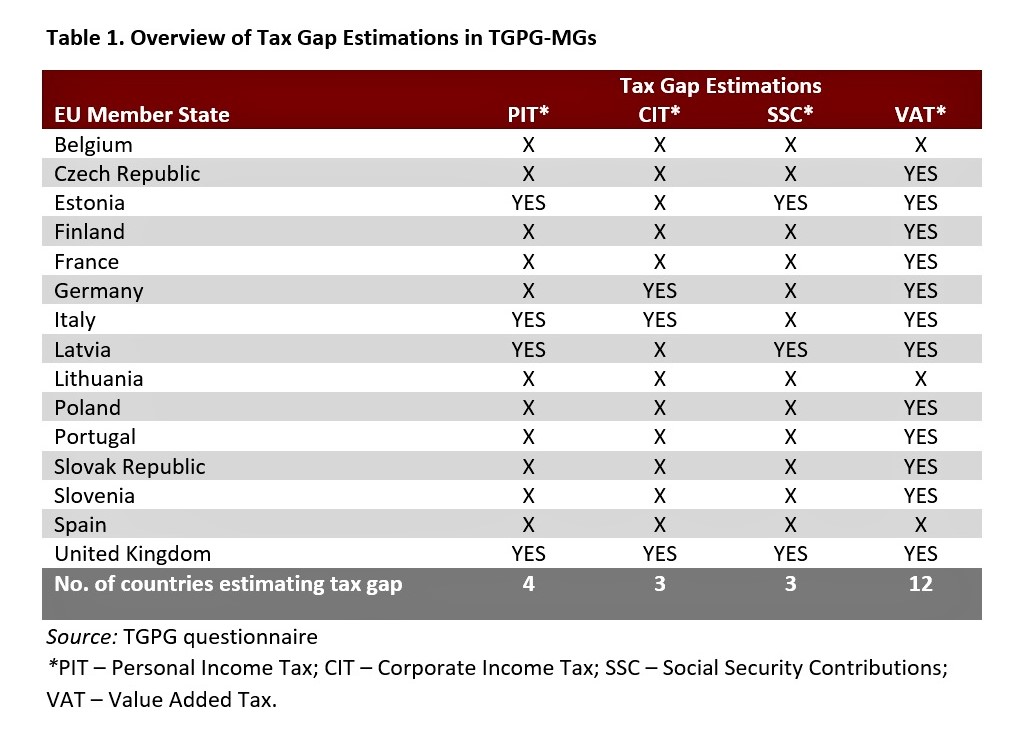

It may be surprising but estimating tax gaps in EU Member States has a relatively short history. The programme for estimating gaps for all major taxes was first launched by the United Kingdom (2008), which publishes data on this indicator every year. In other EU Member States, tax gap estimations are not as comprehensive – nor are they usually made public at the same level of detail – as in the UK. Until 2014, only a few EU Member States other than the UK have established a practice to estimate tax gaps. In order to pool knowledge and experience of the different methodologies by those Member States who produce tax gap estimates and formulating some kind of good practices in this field, the European Commission established in 2014 the Tax Gap Project Group (TGPG). However, even among the countries which are members of the project group, the gap estimations usually cover only VAT (value added tax) (see Table 1).

The project group has prepared two reports so far: Report on VAT Gap Estimations (2016) and Report on Corporate Income Tax Gap Estimation Methodologies (2018). The group considers developing tax gap methodologies for personal income tax (PIT) and social security contributions (SSC) as well but it is also aware that measuring gaps for these types of taxes is more complex. Therefore, it is unclear whether setting up such a project will become a reality.

VAT GAP

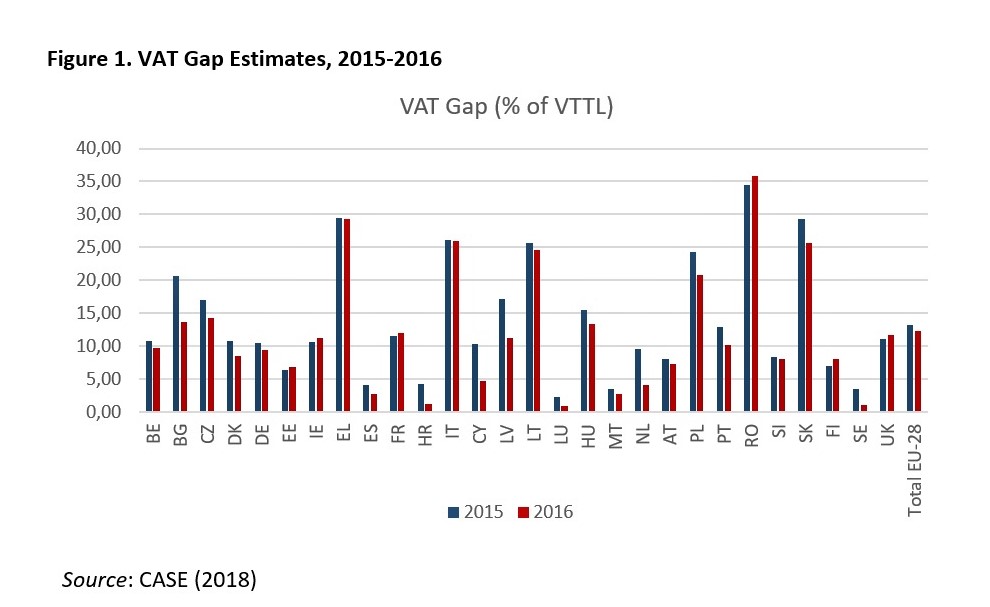

Among the best-known reports covering multiple EU Member States are those concerning estimations of the VAT gap. VAT is an indirect tax and its legal framework is harmonized across the EU. For the past few years, reports estimating the VAT gap for all EU Member States have been commissioned by the European Commission and prepared by CASE-Center for Social and Economic Research. The calculation of the theoretical VAT liability is performed by applying the top-down methodology employed initially by Reckon in the report submitted to the European Commission (2009), modified and upgraded over the years by CASE. The VAT gap, addressed in detail in the CASE reports, refers to the difference between the expected and the actual VAT revenues and represents more than just fraud, evasion and their associated policy measures. The VAT Gap also covers VAT lost due to, for example, insolvencies, bankruptcies, administrative errors, and legal tax optimisation. It is defined as the difference between the amount of VAT collected and the VAT Total Tax Liability (VTTL) – that is the tax liability according to tax law. The VAT gap can be expressed in absolute or relative terms, in the latter case commonly as the share of the VTTL or GDP. A top-down estimate of the VAT gap is based on comparing accrued VAT receipts with a theoretical net VAT liability for the economy as a whole. The theoretical net liability is estimated by identifying and measuring the categories of expenditure that give rise to irrecoverable VAT. The main categories of relevant expenditure that give rise to irrecoverable VAT are final consumption expenditure by households, non-profit institutions serving households (NPISH) and government, intermediate consumption expenditure on goods and services used in making exempt supplies of goods and services, and gross fixed capital formation on assets and changes in the stock of valuables which can be allocated to exempt supplies of goods and services. In its most recent report (2018), CASE presents (VAT) gap estimates for 2016, as well as updated estimates for the period 2012-2016 (Figure 1).

The report shows (see Figure 1) that 2016 was another year in which the VAT gap fell in the European Union in general, although the trends in individual Member States were distributed differently (the highest percentage decline was recorded in Bulgaria, the highest percentage increase in Romania, Poland was ranked sixth in this respect among the countries where the gap fell). In addition to the analysis of the compliance gap, the report examines the policy gap in 2016 as well as the contribution that reduced rates and exemptions made to the theoretical VAT revenue losses. Moreover, the report contains an econometric analysis of VAT gap determinants, which is a novelty compared to the previous editions.

The VAT gap for some Member States has been also estimated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which developed its own method. The IMF Fiscal Affairs Department’s Revenue Administration Gap Analysis Program (RA-GAP) assists revenue administrations from IMF member countries in monitoring taxpayer compliance through tax gap analysis. The RA-GAP methodology for estimating the VAT gap used a value-added approach to estimating potential VAT revenues, as compared to the more traditional final consumption approach used by CASE and most countries undertaking VAT gap estimation. The RA-GAP methodology can provide VAT compliance gap estimates on a sector-by-sector basis, which assists revenue administrations in better targeting compliance efforts to close the gap. In addition, the RA-GAP methodology uses a unique measurement of actual VAT revenues, which isolates changes in revenue performance that might be due to cash management (e.g. delays in refunds) from those due to actual changes in taxpayer compliance. Among the EU countries, the IMF reports cover inter alia Denmark, Estonia, and Finland (see here the report for Finland). Importantly, the IMF’s general VAT gap estimations are convergent with those produced by CASE.

While the EU Member States that estimate the VAT gap usually apply the methodology based on the top-down approach, some of the Member States also use the bottom-up approach (inter alia the UK, Estonia, Slovenia). The bottom-up approach applies techniques such as random sampling of taxpayers for audit or compliance risk analysis and intervention results, which can be used to estimate the impact of specific behaviours. The bottom-up method usually supports top-down estimates.

CIT Gap

The estimation of the CIT gap is less common. It is more challenging to estimate the CIT gap than the VAT gap due to a more complicated relationship between the theoretical CIT base and macroeconomic data. Several methodologies exist for estimating the CIT tax gap. There are two general approaches: top-down methods, also referred to as the macro or indirect methods, and bottom-up methods, also known as the micro or direct methods.

The most standardised methodology for estimating the CIT gap has been recently presented by the IMF and is based on the top-down approach. The IMF’s RA-GAP methodology aims to estimate the potential tax base and the revenues from existing macroeconomic data, taking into account the theoretical differences between the coverage of statistical macroeconomic data and the actual tax base of CIT. The estimated results are then compared with actual declarations and revenues. According to the IMF, this methodology is suitable for initial evaluations of overall CIT non‑compliance in a country.

Bottom-up methods consist of determining the magnitude of non-compliance from data obtained directly from the observation of specific components of the tax. The results and conclusions reached in this way are then ‘grossed-up’ to the whole population using statistical and econometric techniques. This approach can be implemented with different kinds of methods, which can be classified on a double dimension based on information source and data treatment. Various information sources can be identified, such as taxpayer information, enquiries, risk registers, data matching, audits (on randomly selected samples or resulting from the operational activity of the tax administration), compliance controls and checks, questionnaires, and surveys. The data treatment can include different statistic and econometric methods. Using the bottom-up approach, the UK tax administration revealed that for the corporate tax gap, under-declared income is much more important for small and medium businesses than for large businesses. For the largest businesses, the main tax gap issue is avoidance, while under-declared income is relatively unimportant.

It is worthwhile to mention another, alternative, methodology for estimating the CIT gap, which cannot be classified as either top-down or bottom-up. This approach can be used to assess the possible revenue loss via treaty shopping and aggressive tax planning by multinational companies. Using this method, described in the research paper ‘Optimal Tax Routing: Network Analysis of FDI Diversion’, the network of bilateral tax treaties is analysed to identify the route with the lowest tax cost used by the multinational companies with the objective to reduce the tax burden.

PIT Gap

No common methodology has been developed to evaluate PIT gap across the EU. Only a few EU Member States estimate PIT gaps. Some others, including Poland, are interested in engaging in such estimation in the future. The estimation of the PIT gap is as challenging as the estimation of the CIT gap. Like the CIT gap, the PIT gap has numerous causes, including unclear legislation, negligent omissions, differences in interpretation, lack of knowledge and non‑deliberate errors, insolvencies, and, finally, taxpayers’ deliberate actions such as tax fraud, tax evasion and tax avoidance. One principal difference between the PIT and CIT gaps is the scale of tax avoidance, which in the PIT gap is lower than in CIT gap. The estimation of the PIT gap usually focuses on unregistered activities. The two approaches (the top-down and the bottom-up) are applied simultaneously or separately. The top-down approach uses statistical macroeconomic data, while the bottom-up uses results from random or risk-based audits, surveys and micro-studies.

The top-down method is used inter alia by Sweden. It compares national accounts data on households’ use of disposable income for consumption and saving (including the hidden incomes) with what is actually reported in income tax returns and corporate accounting. Various measures are taken in Sweden by the National Accounts to ensure that data on usage reflect reality. After certain corrections (necessitated by the differences in definitions and delimitations) are made, the difference between these two data series gives a rough estimate of unreported income. The discrepancy captures both hidden incomes derived from false accounting (e.g. when private costs are recorded as company costs) and incomes kept entirely outside of the accounting. Moreover, it covers both payments to employees (unreported wages) and non-reported mixed earned income for personal businesses.

The bottom-up method is also used in the UK, where the PIT gap is assessed through two different random enquiry programmes. The first of them, known as the Self-Assessment (SA) programme, is focused on under declaration of tax liabilities by individuals. The term ‘individual’ in this context refers to every person who is obliged to pay personal income tax, including employees, self-employed persons, pensioners, partnerships up to four partners and even those who only have investment income. There is also the Employer Compliance Programme (ECP), which evaluates the tax gap arising from irregularities with Pay as You Earn (PAYE) scheme. Alongside the personal income tax, these programmes also evaluate the magnitude of noncompliance related to national insurance contributions.

The bottom-up method is also used in Italy and Estonia, where the consumption-based method primarily introduced by Pissarides and Weber are applied. This method is used to estimate underreporting of income in micro data collected in the household Survey on Income and Living Conditions (SILC). After controlling for several household characteristics, the method assumes differences in consumption propensities estimated for various income categories.

Conclusions

Although comprehensive reports with tax gaps estimations for the needs of the tax administrations of the EU Member States and the European Commission are a relatively new phenomenon, we observe not only an enormous progress in the methodology of the estimations, but also an increasing interest of the Member States in estimating gaps for new types of taxes.

However, it should be noted that even the most refined methods of estimating the VAT gap do not give specific answers about the reasons for the non-payment of taxes. The current methods for estimating the VAT gap do not allow to decompose it and measure its components like fraud and evasion. It can nevertheless be expected that these shortcomings will be eliminated soon.

The growing interest in the calculation of the CIT gap is a positive phenomenon. It can be assumed that the progress in this area will also include the estimation of the PIT gap and the SSC gap.

All these activities, aimed at systematic and widespread estimation of tax gaps, should contribute to reducing the negative phenomenon of tax non‑compliance.

CASE has been actively involved in this process for several years now, by taking part in the work on the VAT gap study and starting a new project in the area of estimating the PIT gap.