showCASE No. 101 I IT, E-Commerce, and Digital Policies. The Case of Poland

In the recent years, Poland has benefitted from economic openness to see its digital sectors, like the gaming industry, and digitally enabled sectors, such as e‑commerce, develop and thrive. To sustain this development, it is crucial that the digital and digitally enabled flows of goods, services, and data be strengthened even more.

IT

Due to the largely intangible nature of the inputs it uses and the outputs its delivers, the information technology (IT) sector, in particular its software branch, has benefitted enormously from globalisation. With its decentralised value chains, barriers to entry often limited to little more than available skills pools, and access to information encapsulated in its very name, IT the sector can source globally, wherever best talent can be found, and grow by foreign expansion. Consumers likewise benefit, harvesting the savings from the resulting economies of scale as well as from innovative but already well‑established digital distribution channels.

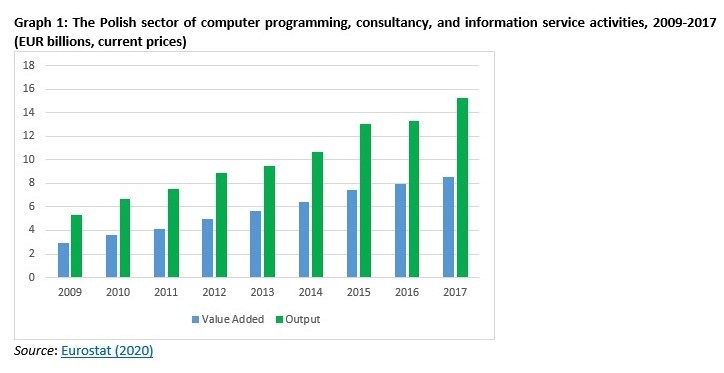

Among the economies that tapped into these opportunities was Poland, which saw its IT sector develop and thrive, with computer services alone generating over EUR 15 billion in output and almost 9 EUR billion in value added in 2017 (Graph 1). Computer services span anything from software developers to entertainment studios to outsourcing centres such as BPO (Business Process Outsourcing) and SSC (Shared Service Centres), which deliver IT services to nearby domestic or far‑away offshore customers. The fast expansion has been enabled by low‑cost, well‑qualified, and English‑speaking domestic workforce, owing to an extensive network of technical universities and high numbers of graduates, fourth largest in the EU28 in the field of information and communication technologies. The country is also a recipient of large amounts of EU funds, which are used, among others, to co‑finance digitisation of services and processes in public administration, propelling domestic demand for IT solutions.

But rather than at bureaucrats’ desks, Poland’s digital expansion is perhaps best seen in a much more entertaining area: the gaming industry. The country is home to several hundred studios, some small and independent, others key players on global markets. One of the giants is CD Projekt, which is the fourth largest company on the Warsaw Stock Exchange’s main index and boasts market capitalisation of PLN 27 billion (EUR 6.5 billion), leaving behind large banks like Pekao, telecommunications behemoths like Orange Polska and mining conglomerates of the sort of KGHM. CD Projekt’s upcoming release, Cyberpunk 2077, famously promoted by Keanu Reaves, is touted as among the most anticipated in the industry. The company’s reputation has been built with the Witcher series, which sold in over 40 million copies worldwide. In fact, the brand name the franchise generated became so symbolic of Poland’s hi‑tech sector that it was a collector’s edition copy of Witcher 2 that the former Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk decided to gift to US President Barack Obama during the latter’s 2011 visit to Poland. CD Projekt is also experimenting with digital distribution channels, having carved out a niche for itself with its GOG.com platform, which specialises in older games in a market otherwise dominated by the US retailer Steam.

While the digital business is running well, CD Projekt and other companies in Polish IT are beginning to face similar challenges as their counterparts in the brick‑and‑mortal sectors. The human capital reserves, which for years have been working to their success, seem to be running out. In line with the general tightening of the labour market in the country and the region, with unemployment most recently (2019 Q3) hovering at 3.2% and persisting below 5% since 2017, skilled workforce is becoming scarce, and wage pressures are high.

E‑Commerce

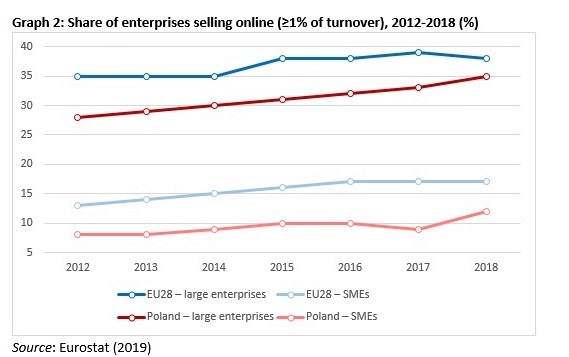

While most companies do not create digital goods or services, they can still profit from digitally enabled distribution channels. In 2018, 35% of large and 12% of small and medium Polish enterprises generated at least 1% of their turnover from online sales (Graph 2). In this, Polish enterprises still trail EU enterprises on average (38% and 17%, respectively), although by margins that are not large and recently dwindling. In fact, 21 e‑stores on average are created in Poland every day, and their total number already exceeds 30,000. Polish e-commerce vendors are typically micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and employ between 5 and 9 (47%) or between 10 and 49 sales specialists (32%).

On the demand side, Poland is home to 27.5 million internet users, corresponding to 83.4% of the population aged 7‑74, and the country ranks strongly as 11th out of 100 in Economist Intelligence Unit’s Inclusive Internet Index 2019. An estimated 62% of Polish internet users, or just over 17 million, made at least one online purchase from a domestic website in 2019 (up from 56% in 2018 and 54% in 2017), and 26% of them also purchased from international websites. Moreover, almost every second Polish internet user (45%) makes an m‑transaction, which involves payment via a mobile device, at least once a week, and transactions struck via social media are gaining in prevalence. Overall, the value of e‑commerce sales was estimated at PLN 50 billion (EUR 12 billion) in 2019. According to e-commerce experts, the share of online sales in general retail trade, at 4.3%, still shows relatively low saturation, and the e‑commerce market will continue to grow toward PLN 80 billion (EUR 19.2 billions) in the next few years.

A factor that favours Polish e‑commerce is the country’s strong transport and logistics sectors, driven by intensive international trade. In fact, Poland, with its substantial domestic market, vicinity of large trading partners, and deep integration with the value chains of Western European industries, has been named among the so‑called leading traders in the World Trade Statistical Review 2019, with an average 4% annual growth in exports in the period 2008‑2018 and a growth in its share in world exports from 0.97% to 1.31% during that time. Such credentials helped attract companies such as US Amazon and German Zalando, which have located their logistics centres in Poland. The former currently operates seven logistics hubs in the country, including a regional e‑commerce facility; the latter has recently launched a fulfilment centre dedicated to 15 million Zalando Lounge members from 13 European countries. Finally, the factor that has been indirectly but significantly supporting the expansion of digital trade in Poland is the recently introduced national ban on Sunday trade.

The Regulatory Framework

Policy makers can either support the development of IT and e‑commerce, by removing any remaining barriers to the free flow of goods, services, and data – or disrupt it, by creating them. In the case of Poland, many policy efforts have fit into the former category. For example, electronic contracts are eligible, and contracts with secure electronic signatures enjoy an equivalent status as paper ones, as per the Civil Code. The Act on the Digital Delivery of Services allows for movables and content to be sold digitally, under the condition that the transaction signed online is documented in a durable form (for example by attaching a receipt to the goods or sending it to the consumer electronically).

Moreover, the European Union’s continued efforts to further integrate the Single Market have helped limit the digital barriers between the Member States. For example, the so‑called eIDAS Regulation, in place since September 2018, ensures that e-signatures from EU countries are mutually recognised. A strategy dedicated to minimizing barriers in cross‑border access to digital goods and services, known as the Digital Single Market, has been launched by the European Commission and already brought many improvements. Unjustified geo blocking has been banned, putting an end to the practice of discriminating online shoppers from EU countries other than those predefined by website operators, for example by charging a higher price. The transparency of cross-border parcel delivery prices has been strengthened, and access to audio-visual services improved by allowing EU citizens to use their online subscriptions in other EU Member States. At the same time, as documented by CASE in its 2019 report, intra‑EU trade in IT services still suffers from restrictions on the flows, usage, and access to data as well as from restrictions on foreign establishment.

Even more serious impediments persist at WTO level, both with regard to data flows and e‑commerce. Indeed, EU citizens encounter considerable obstacles when shopping online outside of the EU. While further talks on data flows and e‑commerce remain important items on the WTO’s agenda, and the EU became a signatory of the WTO’s Joint Statement on Electronic Commerce in December 2017, progress is slow, and the absence of customs duties on so‑called electronic transmissions continues to be regulated by way of a mere moratorium.

In the future, it is desirable from the perspective not only of Poland that the commitment to the freedom of digital and digitally enabled flows of goods, services, and data be continuously strengthened. This will enable further development of IT and e‑commerce, allowing firms to scale by foreign expansion and consumers to access a wide variety of goods and services.

By: Krzysztof Głowacki with contributions from Karolina Zubel, CASE Economists