How Much Did the Federal Reserve Learn from History in Handling the Crisis of 2007-2008?

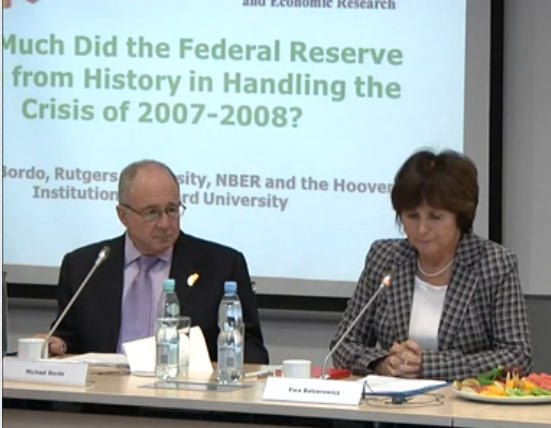

During the 130th mBank – CASE Seminar, professor Michael Bordo discussed the lessons learned from the history of previous financial crises for the monetary policy, focusing mainly on the recent experience of the United States (and namely its Federal Reserve), where the current crisis began. He argued that the crisis of 2007-2008, although widely seen as the worst one since the Great Depression, “was relatively mild compared to what happened in the 1930s” and its effects “were not nearly as bad”. More importantly, though, he claimed that the Fed’s policy during the crisis, based on lessons learn from Great Depression, did not only “not exactly fit the facts of the recent crisis”, but may in fact have “exacerbated the crisis and may have led to serious problems which could contribute to the next (one)”.

During the 130th mBank – CASE Seminar, professor Michael Bordo discussed the lessons learned from the history of previous financial crises for the monetary policy, focusing mainly on the recent experience of the United States (and namely its Federal Reserve), where the current crisis began. He argued that the crisis of 2007-2008, although widely seen as the worst one since the Great Depression, “was relatively mild compared to what happened in the 1930s” and its effects “were not nearly as bad”. More importantly, though, he claimed that the Fed’s policy during the crisis, based on lessons learn from Great Depression, did not only “not exactly fit the facts of the recent crisis”, but may in fact have “exacerbated the crisis and may have led to serious problems which could contribute to the next (one)”.

Professor Bordo argued that Fed has misinterpreted the history by comparing the financial crisis of 2007-2008 to the Great Contraction. In his view, even though Fed’s then chairman Ben Bernanke deemed the two crises alike, they varied significantly. “The signature of the Great Contraction was a collapse in the money supply brought about by a collapse in the public’s deposit currency ratio, a decline in the banks deposit reserve ratio and a drop in the money multiplier”. Throughout the recent crisis, however, M2 did not collapse and the deposit currency ratio in fact rose as the depositors knew their deposits were protected by the state.

As a consequence of this misinterpretation, the policies adopted by Fed did not suit the situation. Liquidity policy – wise, Fed learned from the previous crisis to use “monetary policy to meet all demands for liquidity” and so they “conducted highly expansionary monetary policy in the Fall of the 2007 and since late the 2008”. Since Fed believed that one of the main problems during the 1930s crisis was the wrong credit allocation policy, they adopted one that aimed at providing credit directly to companies and markets that were most in need of liquidity. The consequence of that, prof. Bordo claimed, was the exposure to moral hazard and to the “temptation to politicize the selection of the recipients of its credit”, which in turn negatively affected Fed’s independence.

According to prof. Bordo, the most grave mistakes were made in relation to bailouts. In his view, the crisis might have been possibly avoided had Fed allowed Bern Sterns to fail in March 2008. This would have sent a message to other financial institutions that the Federal Reserve will not save them. What happened instead, was that they received a false sense of impunity from the bailout of Bern Sterns. Consequently, when Fed allowed Lehman Brothers to collapse in September, panic and shock ensued.

According to prof. Bordo, the most grave mistakes were made in relation to bailouts. In his view, the crisis might have been possibly avoided had Fed allowed Bern Sterns to fail in March 2008. This would have sent a message to other financial institutions that the Federal Reserve will not save them. What happened instead, was that they received a false sense of impunity from the bailout of Bern Sterns. Consequently, when Fed allowed Lehman Brothers to collapse in September, panic and shock ensued.

At that point prof. Bordo referred to the interesting fact that as Fed was heavily criticized about their decision, three weeks after Lehman’s bailout, Bernanke “changed his tune” and claimed “there was no way we could save Lehman because it was insolvent and because the Fed did not have the legal authority to rescue it”. What they did next was bailing out and nationalizing AIG, which as prof. Bordo said, brought us back to the problem of a moral hazard problem.

The final lesson discussed by prof. Bordo was related to quantitative easing. According to him, the Fed’s policy in this regard, although it had chances of being successful, was inhibited by their own decision “not to reduce the spread between the interest on excess reserves and the Federal Fund Rate to 0”, which discouraged banks from lending. The situation was worsened by the inconsistency and volatility on the part of Fed in implementing their own policies.

Prof. Bordo argues then, that contrary to Great Depression, the latest crisis was “largely insolvency crisis based on fear of the insolvency of counterparties”. Fed at first misinterpreted the problem and injected too much liquidity into the economy in 2007. Once they realized their mistake, they tried to solve the problem but instead “instituted the credit policies which threatened its independence (…) and engaged a massive bailouts of large interconnected financial institutions that were deemed too big to fail”, which led to a moral hazard for future bailouts. Summing up, the policies undertaken by Fed not only “damaged its credibility” but also “had potentially negative long lasting effects on real economy and on future real growth”.

At the very end of his lecture, prof. Bordo offered his thoughts on the spillover effects of a crisis for emerging markets, which initially were not significantly affected by the crisis as they were not “as exposed to the subprime mortgage derivatives problem”. They were, however, hit hard by a collapse of trade and the fact that they were heavily indebted in hard currency to advanced countries. Prof. Bordo ended his lecture by warning of the negative impact which the ending of Fed’s quantitative easing policy might have on some emerging countries.

Prof. Bordo’s presentation will be included in the 130th mBank-CASE seminar proceedings.

The video of the seminar is available at Bankier.TV.

You can download the PowerPoint presentation here.