A new economic paradigm

One of the main difficulties in economics is to identify turning points in the business cycle. The notion of Credit Impulse tries to solve this issue by focusing on the evolution of the flow of credit. CASE publishes a quarterly update on Credit Impulse for the main global economies and Poland.

Credit Impulse is a relatively new concept based on basic Keynesian economics that emerged in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis and is a key driver of economic growth. Traditionally, economists tend to focus purely on the stock of credit and misses the developments in the flow of credit that are also important to assess the evolution of the global economy. Studies point out that credit impulse is a better credit indicator to understand the business cycle, that is closely related to private demand and that works with a lag of nine to twelve months. In a simple model of economy, the driving forces behind economic growth are consumption and investment. If we assume they are financed by new credit, the best credit indicator related to economic activity is the change in the flow of new credit and not credit outstanding. As the flow of loans is increasing, spending is likely to continue to grow and to fuel economic activity. On the contrary, decelerating credit impulse will produce slower economic activity and negative credit impulse will tend to lead to sharpest slowdowns.

A new paradigm is commonly defined as a new logical framework for understanding a situation. In economy, it often refers to the revision of growth expectations in response to hard data. It is exactly what it is happening. Last week, the OECD made large cuts to its economic forecasts, while calling for central banks to signal low rates for longer. Most importantly, it made the case for a coordinated fiscal stimulus along with structural reforms. Concerns were mostly concentrated on the euro area – Germany’s GDP is expected to reach only 0.7% this year while Italy may be headed for the worst year since 2013. However, looking at a larger scale the economic outlook is not brighter in other parts of the developed world. Trade data, like the Harpex TEU index and the Baltic Dry index, are in contraction. The semiconductor industry, which serves as proxy of global growth, is going through a rough time. Global sales receded 5.7% on the year to January. Such a bad figure marks the first decline in 30 months. In addition, OCDE private sector confidence has sharply decreased since Q3 2017. Though surprised at first, policymakers have quickly realized that they need to step in to stimulate the economy. As a result, central banks are shifting out of normalisation mode, as demonstrated by the Fed pause and the new TLTROs launched by the ECB, but they are not ready to reverse monetary policy yet. Except for China, which has massively opened the credit tap since 2018, the flow of new credit is still moving lower in most of the main economies, notably in the United States and in the United Kingdom. In other words, it means we should expect low growth for at least the next nine to twelve months. However, as macroeconomic data will continue to disappoint, our central scenario for H2 2019 is that governments will have no other choice than resorting to fiscal expansion to strengthen the economic activity.

Country-by-country analysis: Lower for longer

In this update, we would like to focus on four main economies that we pay attention to in 2019: The United States, the euro area, the United Kingdom and Poland.

US credit impulse sends a warning signal about growth

First, the United States. 2019 GDP growth is doomed to decelerate sharply to 2% due to lower personal consumption, ongoing slowdown in housing investment and contraction in credit impulse. Looking at GDPNow from Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, GDP growth is expected to be soft in Q1, reaching only 0.2%. The slowdown should continue since there are less new credit in the economy to serve as growth engine. US credit impulse has experienced quite a swing over the past six quarters: in Q2 2017 it was running at 2.4% of GDP and it is now at minus 2.2% of GDP, the lowest quarterly level since the GFC. The US OECD leading indicator, which is designed to anticipate turning points in the economy six to nine months ahead, also confirms the scenario of slowdown. The year-on-year rate is in contraction, at minus 0.4%. At the same time, the risk of recession, though tricky to precisely forecast, has also significantly increased in the space of three months according to the NY Fed’s recession-risk model which looks at the difference between 10-year and three-month Treasury rates. It was at 15.8% in November and jumped to 21.4% in December before reaching 23.6 in January, which is the highest level since summer 2008.

Waiting for fiscal expansion in the euro area

Second, the euro area. The economic situation is more worrying than in the United States as the euro area has not fully recovered from the GFC and its banking system is fragile in some countries. We notice big declines in the industrial production data for the main European economies, including Germany which accounts for one third of European industrial activity. This negative trend is explained by low sentiment in the automotive industry, China’s slowdown and decreasing credit impulse. At the euro area level, credit impulse is back in positive territory, running at 0.4% of GDP, after a negative print at the beginning of 2018. However, the positive pulse remains very small compared with its four-year average of 0.8%. What is even more concerning is the distinct deceleration in credit impulse in the periphery of the euro area. It is close to zero in Italy and it is sinking more and more into negative territory in Spain, at minus 2.1% of GDP, a level that had not been reached since the end of 2013. It clearly confirms what we have said in previous analysis: the euro area has entered into a more restrictive credit cycle that will have negative impact on domestic demand – as it is highly correlated to the flow of new credit in the economy – and, ultimately, will result into low growth and further stimulus from the ECB (after the new round of TLTROs, another measure widely discussed by ECB watchers could be to push the depo rate back to zero to reduce negative pressure on the banking sector) and fiscal expansion in H2 2019.

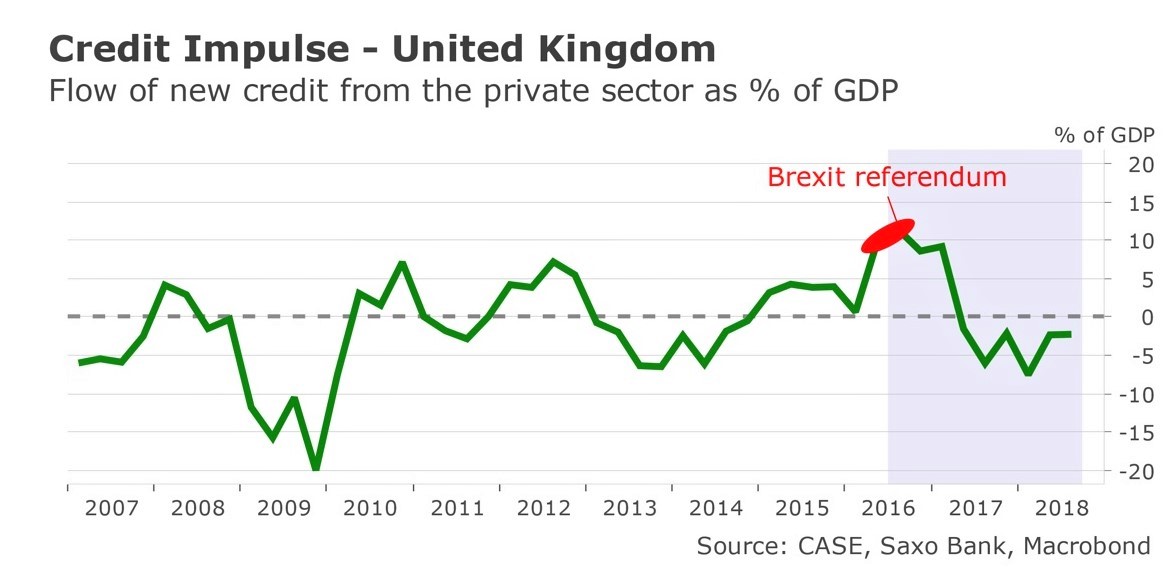

The lack of new credit growth is hitting the British economy

Thirdly, the United Kingdom. As we all know, Brexit soap opera will likely continue for a while. In the meantime, the British economy is falling apart. UK credit impulse is running at minus 2.2% of GDP, one of the weakest level in developed countries. It went through five consecutive quarters of contraction since the Brexit referendum and experienced its biggest quarterly drop since the GFC in Q1 2018, evolving at minus 7.5% of GDP. We can see very well in the chart below that the negative trend in new credit flow started at the same time than the 2016 referendum and accelerated as difficulties to find a middle-ground between the UK and the 27-EU appeared. Currently, the United Kingdom’s top issue is the lack of new credit growth as main driver of economic activity. As household consumption is also fading, growth outlook for the country is deteriorating very fast for at least the next 6 to 9 months.

Fiscal pulse and credit impulse are driving the Polish economy

Fourth, and finally, we cover Poland. Credit impulse is accelerating at 6.2% of GDP, its highest level since the end of 2011. Though 2018 Q4 GDP growth slightly decelerated to 4.9% YoY, growth dynamics are still very well-oriented. So far, the country has managed to offset the negative consequences of lower global trade and low growth in the Eurozone. We are confident that the spur in new credit flow along with the fiscal impulse announced by the government that could bring 0.6ppt to GDP in 2019 will mitigate the negative impact of external factors and push YoY GDP around 4% this year. The bottom line is that growth will be driven solely by consumption and not by private investment as Germany’s slowdown and rigorous tax policy will limit incentives to invest.

By Christopher Dembik, CASE Fellow